Author Bio: Dr. Ram Prakasha BPTh

Written by a Physiotherapy and Public Health professional with experience in neurological rehabilitation and health awareness. The content is intended for educational purposes only.

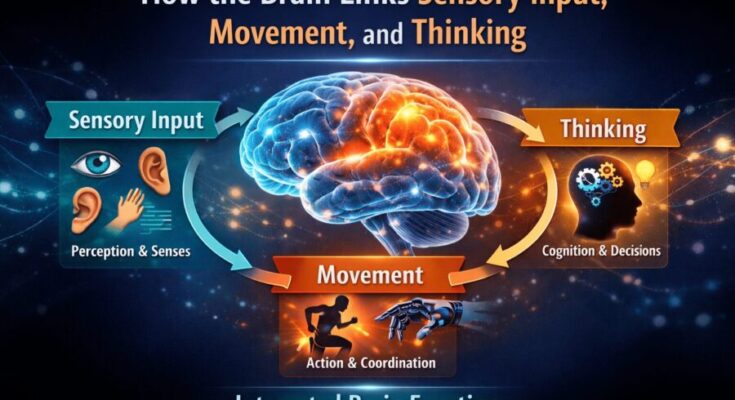

Brain sensory motor integration

Understanding how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking has become one of the most fascinating topics in modern neuroscience. For decades, scientists believed that sensation, action, and cognition were mostly separate processes. However, recent evidence shows that these functions are deeply interconnected. In fact, the brain constantly integrates what we sense, how we move, and what we think into a single, continuous loop.

Therefore, this blog explores how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking, using strong neuroscientific evidence. Moreover, it explains why this connection is essential for learning, decision-making, and everyday behavior. Additionally, it highlights how this understanding is reshaping rehabilitation, education, and mental health practices.

The Brain as an Integrated System

Traditionally, the brain was described in isolated parts. For example, sensory areas processed input, motor areas controlled movement, and cognitive regions handled thinking. However, modern neuroscience clearly shows that this division is overly simplistic.

Instead, the brain works as an integrated network. Therefore, sensory information influences movement, movement shapes thinking, and thinking alters perception. As a result, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking reflects a continuous feedback system rather than a linear pathway.

Furthermore, brain imaging studies demonstrate that multiple regions activate simultaneously during even simple tasks. Consequently, this supports the idea that perception, action, and cognition cannot be separated.

Sensory Input: The Foundation of Brain Processing

First and foremost, sensory input provides the brain with information about the external and internal world. Vision, hearing, touch, taste, smell, and proprioception all deliver constant streams of data.

However, sensory input is not passively received. Instead, the brain actively predicts and interprets sensory signals. Therefore, perception is shaped by expectations, memory, and attention.

Importantly, studies show that sensory areas are active even when we imagine movement. Thus, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking begins with the brain’s predictive interpretation of sensory signals.

Movement Shapes Sensory Processing

Interestingly, movement does not simply follow sensory input. Instead, movement actively modifies how the brain processes sensation.

For example, when you reach for a cup, your brain predicts the sensory outcome of that action. Consequently, the sensory cortex adjusts its sensitivity before contact occurs. Therefore, movement prepares perception in advance.

Moreover, experiments demonstrate that restricting movement can impair perception and cognition. As a result, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking becomes clear: movement is essential for refining sensory accuracy.

Thinking Emerges from Action and Perception

Traditionally, thinking was viewed as an abstract process separate from the body. However, neuroscience now supports the concept of embodied cognition.

In other words, thinking arises from interactions between the brain, body, and environment. Therefore, cognitive processes such as reasoning, planning, and problem-solving are deeply grounded in sensory and motor systems.

For instance, brain scans show that motor regions activate during mental arithmetic and language processing. Consequently, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking highlights that cognition depends on sensorimotor networks.

Neural Pathways Connecting Sensation, Action, and Cognition

Neuroscientific evidence identifies several pathways that explain this integration.

The Sensorimotor Cortex-Brain sensory motor integration

The sensorimotor cortex integrates sensory feedback and motor commands. Therefore, it allows smooth and adaptive movement.

Moreover, damage to this area disrupts both perception and cognition. As a result, it provides strong evidence for how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking.

The Cerebellum

Once thought to control only coordination, the cerebellum is now known to support attention, learning, and planning.

Consequently, cerebellar activation during cognitive tasks demonstrates that movement-related structures contribute to thinking.

The Basal Ganglia-Brain sensory motor integration

Similarly, the basal ganglia play a role in movement selection and decision-making. Therefore, they connect physical action with cognitive evaluation.

Learning Depends on Sensory-Motor Interaction

Learning is one of the clearest examples of how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking.

For example, children learn better when they move, touch, and interact with their environment. Therefore, active learning strengthens neural connections.

Additionally, studies show that physical activity enhances memory and attention. As a result, movement stimulates brain plasticity and cognitive growth.

Neuroplasticity and Integrated Brain Function

Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to change and adapt. Importantly, sensory input and movement are major drivers of plasticity.

For instance, learning a musical instrument reshapes sensory, motor, and cognitive regions simultaneously. Consequently, this demonstrates how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking through experience-dependent changes.

Moreover, rehabilitation programs use movement-based therapies to restore cognitive function after injury. Therefore, integrated brain training is more effective than isolated mental exercises.

Evidence from Brain Imaging Studies-Brain sensory motor integration

Functional MRI and EEG studies provide compelling evidence for integrated processing.

For example, when participants perform tasks involving planning, multiple sensory and motor areas activate together. Therefore, thinking recruits systems traditionally labeled as “non-cognitive.”

Furthermore, resting-state studies show constant communication between sensory, motor, and cognitive networks. As a result, the brain remains integrated even at rest.

The Role of Attention and Prediction

Attention acts as a bridge between sensation, movement, and thinking. Therefore, what we attend to shapes how we move and think.

Additionally, predictive processing models suggest that the brain continuously anticipates sensory outcomes of actions. Consequently, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking depends on prediction and error correction.

When predictions fail, learning occurs. Thus, action and perception drive cognitive updating.

Implications for Mental Health

Understanding how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking has major implications for mental health.

For example, depression and anxiety often involve reduced movement and altered sensory processing. Therefore, physical activity and sensory-based therapies improve mental well-being.

Similarly, mindfulness practices integrate body awareness, movement, and cognition. As a result, they strengthen brain connectivity and emotional regulation.

Applications in Education-Brain sensory motor integration

Educational neuroscience emphasizes movement-based learning. Therefore, classrooms that encourage physical engagement enhance attention and memory.

Moreover, gestures support language comprehension and problem-solving. Consequently, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking explains why active learning is more effective than passive listening.

Rehabilitation and Clinical Neuroscience

In rehabilitation, movement is used to restore thinking abilities.

For instance, stroke patients regain cognitive function through motor training. Therefore, sensory-motor therapies promote brain reorganization.

Additionally, virtual reality rehabilitation combines sensory input, movement, and cognition, offering powerful recovery tools.

Evolutionary Perspective

From an evolutionary standpoint, thinking evolved to guide action. Therefore, cognition is fundamentally linked to movement and survival.

Early brains processed sensory information to coordinate movement. Consequently, abstract thinking developed from these basic functions.

Thus, how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking reflects millions of years of evolutionary adaptation.

Future Directions in Neuroscience

Future research will further explore integrated brain models. For example, brain-computer interfaces rely on sensory-motor-cognitive integration.

Moreover, artificial intelligence increasingly mimics embodied cognition. Therefore, understanding how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking will shape future technologies.

FAQs: How the Brain Links Sensory Input, Movement, and Thinking

1. What does it mean that the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking?

It means that perception, action, and cognition are interconnected processes that continuously influence each other rather than functioning separately.

2. Why is movement important for thinking?

Movement activates brain networks that support attention, memory, and problem-solving, making cognition more effective.

3. How does sensory input influence decision-making?

Sensory information provides context and feedback that guide predictions, choices, and actions.

4. Can improving movement improve cognitive function?

Yes. Physical activity enhances neuroplasticity and strengthens cognitive performance.

5. How does this concept help in rehabilitation?

Rehabilitation programs use sensory-motor training to restore thinking and perception after neurological injury.

6. Is this idea supported by neuroscience research?

Yes. Brain imaging, lesion studies, and behavioral experiments all support how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking.

Conclusion

In conclusion, neuroscience clearly demonstrates how the brain links sensory input, movement, and thinking into a unified system. Rather than operating in isolation, these processes form continuous feedback loops that shape perception, action, and cognition.

Therefore, understanding this integration transforms how we approach learning, rehabilitation, mental health, and human performance. Ultimately, the brain is not just a thinking machine but an embodied, adaptive system designed to interact with the world.